2008 Biennale of Sydney, “Revolutions- Forms that Turn”

With the 2008 Biennale of Sydney, “Revolutions— Forms that Turn,” Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev attempts to set a new direction for the international art biennale. Her curatorial strategy—to mix historical works with recent art—rebels against what she sees as a surplus of international biennales that have become the equivalent of shopping malls of culture, devoted to the “cult of the new.” As she writes in her catalogue essay, she desires “to create a constellation of past and present that rebukes the need for ‘novelty,’” and instead concentrates on the “politics of aesthetics.”

Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, The Murder of Crows, 2008, sound and mixed-media installation with audio speakers, amplifiers, computer, electronics, miscellaneous media, 30 minutes. Installation view in 16th Biennale of Sydney, 2008 at Pier 2/3, Walsh Bay. Courtesy the artists, Luhring Augustine, New York, and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin. Photograph: Greg Weight.

Christov-Bakargiev’s curatorial vision has translated into a critically engaging Biennale. At times however, it is overburdened with classics from the historical avant-garde of the 20th century—many of which, like Duchamp’s The Bicycle wheel, 1913, and Manzoni’s Merda d’artista, 1961, have been seen all too often. At the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) and the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), historical works tend to dominate the constellations of art. For instance, at the AGNSW, Francis Alÿs’s tragic-comic video Choques, 2005–06, of a man tripping as he walks down the street, is overwhelmed by the abundance of works by historical heavyweights like Joseph Beuys, Jean Tinguely and Yves Klein.

Michael Rakowitz, White man got no dreaming, 2008, drawings, salvaged building materials, video, radio transmitter. Installation view in the 16th Biennale of Sydney, 2008 at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Courtesy the artist and Lombard- Freid Projects, New York. Photo: Jenni Carter.

Artists addressing the Biennale’s theme of political revolutions tilt toward a rehash of the history and impact of the Russian Revolution on radical art making in the 1930s and ’40s. Recent works by Yevgeniy Fiks, Peter Watkins and Susan Philipsz seem to yearn for the old days of radical collective action. An exception is Michael Rakowitz’s massive wooden tower, White man got no dreaming, 2008. Inspired by Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International, and installed at the entrance to the AGNSW gallery, Rakowitz actually puts the ideology of socialism into practice. The tower is made from recycled housing material originally owned by the Aboriginal Housing Company in Redfern, Sydney, and built with help from the Redfern community. Cockatoo Clock (A Play), 2008, Geoffrey Farmer’s subversive intervention into the spaces between the gallery walls at the MCA—composed of odds and sods scavenged from Cockatoo Island and elsewhere— proposes that today’s revolutionary art is all about infiltration rather than confrontation.

William Kentridge, I am not me, the horse is not mine, 2008, 40-minute lecture/performance with projection. Courtesy the artist, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York and Paris, Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg, and Annandale Galleries, Sydney.

The three works at Pier 2/3 form one of the more successful clusters of historical and contemporary art. Dominating the huge warehouse space is the sound installation Murder of Crows, 2008, by Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, one of the highlights of the Biennale. The installation consists of 100 speakers placed on the floor and on wooden folding chairs set in a circle around an old gramophone speaker that rests on a battered card table. Cardiff’s lethargic voice murmurs from the gramophone speaker, recounting terrifying scenes from a nightmare. Her narrative, accompanied by a complex audio track that includes music, bird noises and the splash of waves, creates a powerful shift in perception from the visual to the aural imagination. Sharing Pier 2/3 with Cardiff and Bures Miller is a facsimile of Luigi Russolo’s fascinating noise-making machines, Intonarumori, c. 1913, an early attempt to collapse the distinction between sound and noise. A beautiful (untitled) abstract painting by Western Australian artist Doreen Reid Nakamarra reverses the play of perception from sound back to sight. Placed on the floor, the painting’s motif of brown zigzag lines read as a metaphor for the waves of valleys and ridges in the desert landscape.

Geoffrey Farmer, Cockatoo Clock (A Play), 2008, installation view in the 16th Biennale of Sydney, 2008, at the Museum of Contemporary Art. Courtesy the artist and Catriona Jeffries Gallery, Vancouver. Photo: Jenni Carter.

For the first time, Cockatoo Island, a short ferry ride from Pier 2/3, is a venue for the Biennale of Sydney. A former prison and now abandoned shipbuilding centre, the island’s derelict buildings were filled with videos, films and site-specific installations. Some works, however, looked lost in the industrial wasteland setting of the island, like Brian Jungen’s witty mobile made of Samsonite luggage transformed into Australian animals. It belonged at the MCA with other mobiles by Rodchenko, Calder and Danish artist Olafur Eliasson that traced the evolution of this radical art form.

Geoffrey Farmer, Cockatoo Clock (A Play), 2008, installation view in the 16th Biennale of Sydney, 2008, at the Museum of Contemporary Art. Courtesy the artist and Catriona Jeffries Gallery, Vancouver. Photo: Jenni Carter.

Two exceptional works on the island by South African artist William Kentridge embraced the Biennale’s theme on a multitude of levels. I am not me, the horse is not mine, 2008, is a multi-channel projection based on The Nose, 1837, a story by Nikolai Gogol. The projections are an engaging mix of sound and media, featuring Kentridge’s signature drawings, paintings and newspaper collages, in which the viewer follows a large black nose as it scampers up a fire escape, plays piano and dances on stage, like a character from a theatre of the absurd. It is a riveting piece to watch as it explores, among other things, the nature of totalitarian political propaganda through the lens of Stalin-era communism.

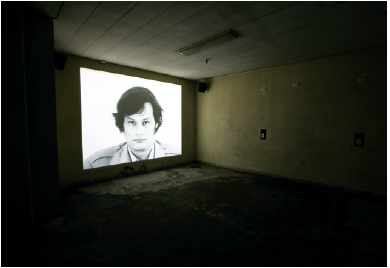

Mike Parr, MIRROR/ARSE, 1971/2008, detail from installation at Cockatoo Island for the 16th Biennale of Sydney, 2008. Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Sydney and Melbourne. Photo: Jenni Carter.

Kentridge’s other work is the world’s first anamorphic film projection, What Will Come (Has Already Come), 2007. This remarkable piece consists of a series of spinning anamorphic drawings of carousel animals, tanks, people and aeroplanes, projected onto a round table. The blurred images are resolved in a cylindrical mirror at the table’s centre. The technological magic alone makes this an outstanding work. However, the film’s entertaining quality is offset by its horrific subject: the Italian aerial bombardment with mustard gas of Abyssinia in 1935–36 that killed an estimated 30,000 people.

Mike Parr, MIRROR/ARSE, 1971/2008, detail from installation at Cockatoo Island for the 16th Biennale of Sydney, 2008. Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Sydney and Melbourne. Photo: Jenni Carter.

Also on the island is an excellent mini-retrospective of Mike Parr’s performances over the last 20 years titled MIRROR/ARSE. The suite of 14 filmed performances is presented on video monitors installed in a rabbit warren of rooms in a building that reeks of urine, the odour emanating from pails that are part of the installation. A truly radical artist, Parr’s self-inflicted wounds speak to the tyranny of the body and its agencies of pain in performances that often confront the politics of race in Australia.

For the first time, the Biennale has an online space: www. bos2008.com/revolutionsonline. The website is an important addition as it acknowledges a truly revolutionary medium still in its infancy. UK artists Stanza, for example, exploit the real-time possibilities of the Internet in Urban Generation, 2002–05, a tapestry of images woven from live CCTV cameras that watch London’s streets. Revolutionsonline provides the opportunity for a seamless, chaotic interplay between the art of the past and the present, and possibly is the best expression of Christov-Bakargiev’s vision for the 2008 Biennale. ■

The 16th Biennale of Sydney, “Revolutions— Forms that Turn,” was held in Sydney, Australia, from June 18 to September 7, 2008.

Robert Epp is the gallerist for Gallery One One One at the University of Manitoba School of Art in Winnipeg. He is currently on a one-year leave of absence and living in Australia.