2007 Alberta Biennial of Contemporary Art: “Living Utopia and Disaster”

If the Alberta Biennial of Contemporary Art began on a dark note with Robin Arseneault’s Paradoxe sur le comédien, perhaps it is because Alberta is a tough place to make a practice. The appropriately dubbed “Living Utopia and Disaster” suggests opposing forces of beauty and destruction, but many of the 40 works in the exhibition hover somewhere in-between. This tension began with Arseneault’s theatre of absurdity. The installation was demarcated by black paper ceiling flags, and flanked by bleachers full of cardboard boxes personified by cut-out facial features, plastic snouts and masks. The centre of their attention was a wimpy, animated doodle projected on an old-style screen and they seemed to express a hollow dismay at the false spectacle of the animation. When standing outside the scene, as a member of the audience, there was a great temptation to view the tragicomic work as a metaphor for the uncertain or devalued role of the contemporary artist in this province. Do we want to shock, awe and provoke? What about making spaces for prettiness and gentle reflection? Is the exhibition a timely statement or an enduring conversation? Who’s listening? These are questions to take into any Biennial.

Terrance Houle and Jarusha Brown, Landscape 1, 2007, colour photograph mounted on aluminium, 3 x 5’. All images courtesy Alberta Biennial.

Curatorial team Catherine Crowston and Sylvie Gilbert took pains to introduce a refreshing cast of new artists into the mix, and this is likely the best news for the exhibition’s 2007 incarnation. Since its inception in 1997, the Biennial has nurtured new generations of Alberta artists alongside the old stalwarts, and renewal is in the air with strong showings by emerging artists Anu Guha Thakurta, Terrance Houle and Jarusha Brown, Kristy Trinier and Sarah Adams-Bacon, among others.

Brown and Houle’s three highly aestheticized landscapes evoke the Vancouver School, until we see that something has gone awry: an Aboriginal figure—so often erased from the prairie landscape—plays dead amid piles of chopped-off sod at the outskirts of a baseball game, lies face-down under a suburban tree while two ladies picnic and is passed out behind a family in traditional regalia. Once Houle’s performative prank comes into view, it’s hard to ignore his figure, and even harder to ignore the humour with which he upturns stereotypes.

Geoffrey Hunter, Moonshiner’s Dance, 2007, oil on canvas, 72 x 66”.

Alongside these collaborative landscapes, works by Laurel Smith, Paul Freeman and David Janzen’s Loft (A) and Loft (B) conjure beautiful, imaginative places, and veer sharply away from the sci-fi-inspired spaces in TRUCK Gallery’s similarly named summer exhibition, “Salvaging Utopia.” With Kay Burns’s technically assisted conversation platforms in Converse, or Annie Martin’s claustrophobic Nervous Space, the technophobic meet their match. Martin transmits ambient sound from the gallery lobby through tiny portals in the enclosed room, but get in the way of the speakers and you’ll swear it’s busy freeway traffic or a roaring Alberta tornado.

The sound bleed emanating from March is problematic for viewing Richard Boulet’s curiously stitched quilts, but the blind approach to Ken Buera’s video expertly gives preference to audio over the image. The methodical “music” accelerates until the beat almost provokes a shaky robot shimmy into the room. Once this soundtrack is absorbed, the images that appear projected are even more legible as the daily rhythms of a commercial print shop are remixed for speed. The work’s impact owes much to the excellent curatorial decision to locate it in the back of the gallery.

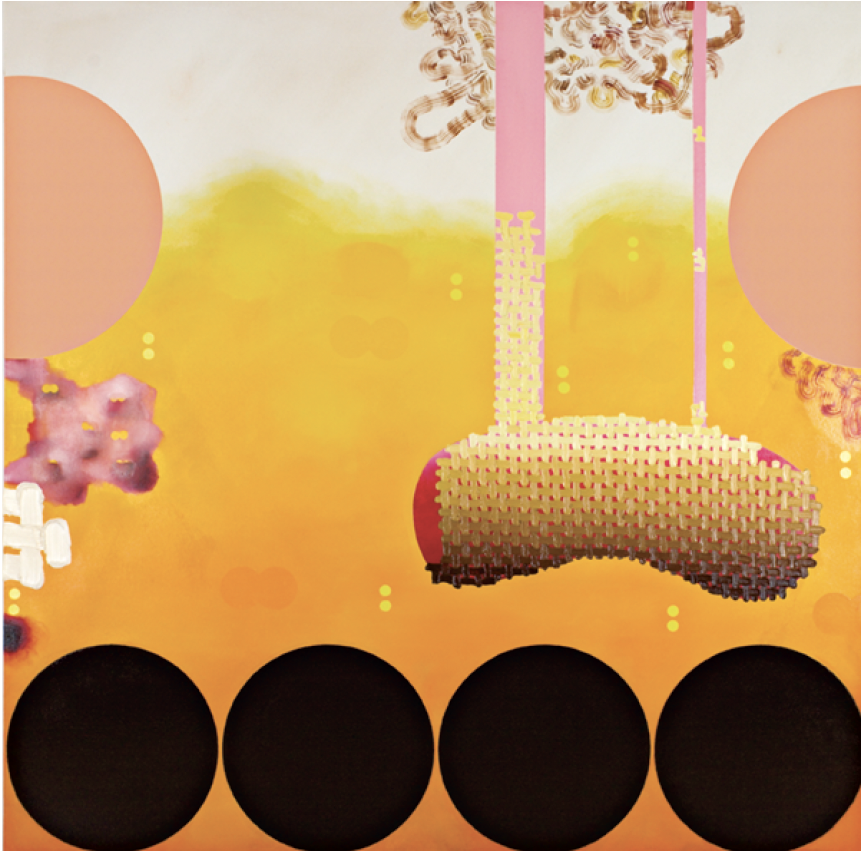

Mark Mullin, Absorption Rates II, 2007, oil on canvas, 6’ x 6’ x 4”. Courtesy Paul Kuhn Gallery, Calgary.

A discreet doppelganger for the front entrance of a home is tucked into the back quarter too. Lost Boys and the Hundred Year Mortgage by Jonathan Kaiser is perhaps one of the most convincing contemporary riffs on the cabinet of curiosity, with all its carefully coded narrative clues to be found in buckets, cobwebby corners and aquariums modelled like empty little modernist habitats. Despite reading like a The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe-type intermediary zone, it’s one of the more literal commentaries on Alberta’s hot-button housing crisis.

The charm of the Art Gallery of Alberta’s temporary gallery space appears again in the skilled installation of Mary Kavanagh’s seamless postcard-sized video portals sunk into the wall. By rendering these worlds miniature—particularly in the face of large-scale video projections like Buera’s that have been in vogue—she conveys a sense of voyeurism and nostalgia. Characters in her Travel Notes 27.06.06 White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico seem at times anxious or self-conscious: tourists on this makeshift “beach” pack up and leave, just as the camera establishes a shot on them. And anxious they should be—atomic testing began at the site in 1945 and continues today.

David Janzen, Welcome to Arcadia, 2007, oil on canvas, 6 x 8’. Courtesy Paul Kuhn Gallery, Calgary.

Paintings by Mark Mullin and Geoffrey Hunter are hung directly across the gallery space from each another. A viewer can’t help but ping-pong between the pairing of these two established painters, two stable-mates from Calgary’s Paul Kuhn Gallery. Mullin’s is a meticulously formulaic vocabulary of paint—discs of colour and cross-hatches hovering over soft pastel hazes on extra-deep canvases, where Hunter’s curvilinear, moody canvases cast a darker scene of encompassing, terrestrial tunnels in restrained colour.

Even showings of painting, drawing, new media and textiles, to name a few, are a radical departure from the bombastic, large-scale sculpture and installation that dominated previous Biennials. Because of this, “Living Utopia and Disaster” could almost be dubbed the “business as usual” Biennial if it weren’t for the works that triumphantly prove art doesn’t have to be gigantic to deliver a show-stopping experience.

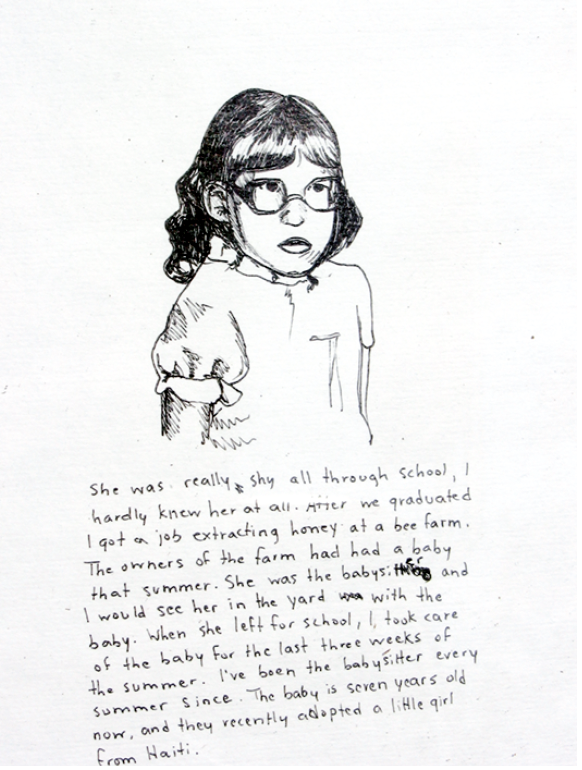

Sarah Adams-Bacon, “Everything was Beautiful and Nothing Hurt” (Drawing Series), 2004, ink on paper, one of 36 drawings, 10 x 12” each.

In the decade since the Biennial began, I’ve never heard one pronouncement that the selected works represent “the best of Alberta art,” or a picking of favourites. Instead, a solid curatorial involvement in the arts communities, an open submission call and a full roster of studio visits throughout the province suggest a methodical dedication to the artists who choose to locate their practices in Alberta. Given the number of Alberta artists responding to the problems of a booming provincial economy, using the energetic, political and outspoken media of performance, intervention and site-specific projects, the Biennial’s history of sidelining these practices seems particularly shortsighted this go-round. But then perhaps the majority of artists who are working in these streams choose to live in other places. Or, like the conspicuous absence of creatures in Kaiser’s aquariums, they hail from Alberta but have fl ed in search of more hospitable spots to call home. That’s one tragedy our Biennial only begins to convey. ■

The 2007 Alberta Biennial of Contemporary Art: “Living Utopia and Disaster” was exhibited at the Art Gallery of Alberta in Edmonton from June 23 to September 9, 2007, and at the Walter Phillips Gallery in Banff from October 27, 2007, to January 6, 2008.

Anthea Black is an artist, art writer and cultural worker based in Calgary, Alberta.