1987: Contemporary Art in Manitoba

1987: Contemporary Art in Manitoba is not an ordinary anniversary show. Rather, it’s a veritable Monumenta of work alchemically organized to encourage viewers to experience the conditions under which, as curator Shirley Jayne-Raven Madill says, “patterns of production” dance off the walls and cruise around the spaces created by juxtaposing media, materials and styles of art-making. It’s an exhibition that talks back, and does much to inspire viewers to do the same.

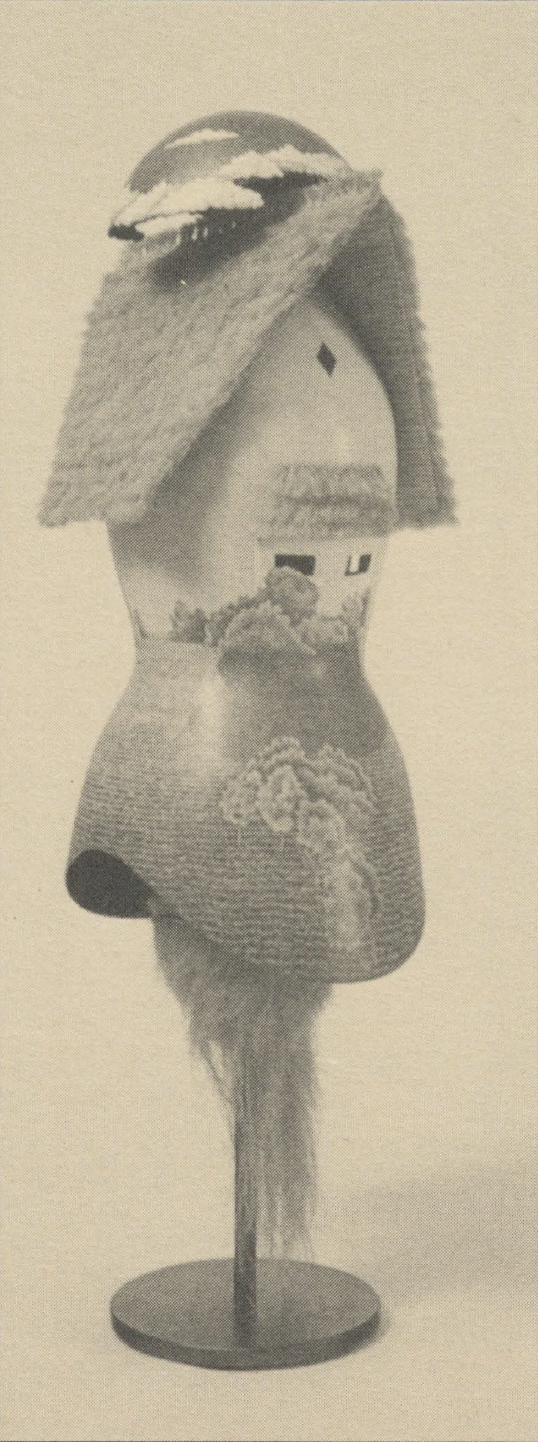

Look at Don Proch’s piece. An ancestral mask by the god father of a certain kind of Contemporary Prairie, Post-Landscapist conceptual, but-often-figurative, Regionalism, is a good-humoured, fitting and challenging beginning to the 1987 show. But, when facing a god father figure, one does well to look over one’s left shoulder … and sure enough, over one’s left shoulder: large, almost orthodox, paint on canvas works with human figures and narrative—even epic—subject matter. Their very size draws you back from the official entrance and gives you pause to reconsider the exact parameters of time and the spaces that the 1987 show represents. The more so because the large canvas diametrically opposed (in space) to the bulk of the work literally situated behind the ancestral masked entrance is called How the Iron Age Began (Susan Chafe); and, it incorporates a decorated (but unfinished) frame inside its own framelessness. (Post-Symbolist conceptual representation, maybe?)

On the main level you may have wondered: ‘Hockey masks, high-rise model trains sweeping low, violins called Black Water, a baby grand piano: is this 1987? And Mini Davis’ fiery steel sculpture, Legend of a Telling Man, outside the gallery, is this 1987 too?’ 1987 is not devoid of humour. Nor is it devoid of a collage/montaged sub-text of dialogues, ideas, questions and images about the making of art— “patterns of production,” to use curator Madill’s language.

Mini Davis, Legend of a Telling Man, 1987.

As you look around you’ll have to admit it’s the spirit and energy of the art that actually projects your imaginative experience of it—convincing you that 1987 (The Exhibition) is deliberately play/acting on more stories (levels) than one—in much the same way as do many of the individual works. Multiple Realities is the new realism of 1987. The 1987 show is a vessel for containing everything (almost) you ever wanted to think about contemporary art in Manitoba. No sooner do we find our eyes bouncing back and forth between the greens of Sheila Butler’s dreamy, figurative Long Distance, to Diane Whitehouse’s abstract, landscaped Hill, than we hear Doug Melnyk’s voice like a shadow, performing a found fragment from the relative isolation of his listening-room installation. The found fragment hovers invisibly between the refrigerator’s (Aganetha Dyck, Crossley Moffat) fantastic contents, and the juxtaposition of a photographic portrait (Larry Glawson, Untitled, or Doug and Terry) with a portrait painted from a photograph (Myron Turner, Gaby and Bob). The four of them stare past us, towards a back wall where a carefully cropped, painted version of an oversized contact sheet documents a Morning Suite (Betty Woodland) for two figures, in which the gazes are directed not towards us, or the rest of 1987, but towards the art on the wall of the painting itself.

For Madill, it can not have been an easy task to organize this mountain of contemporary art in such a way that neither narrative threads, nor possibilities for appreciating the uniqueness of individual works, were lost. That the dialogues about art, materials, media and methods which emerge do not intrude upon the possibilities for seeing and sometimes marvelling at the uniqueness of individual works is a tribute to both the power of the works themselves and to the genius of the creative principles underlying the pluralistic patterns of production. For example, Esther Warkov’s Einstein Before the Ark, His Hair Beginning to Stand on End could stand alone to say, with great ingenuity and skill, that there is a specific kind of timeless irony, with or without high-tech, in the epic of human creation and atomic destruction. In the 1987 show there’s a new resonance that both enhances the work and encourages us to see more in works like Enter Spirits Laughing (Tom Lovatt) or Thief (Marsha Whiddon). In the same way, neither are the delicately transparent vessels of glass containing and refracting light diminished by being surrounded by three walls of photographs, a medium that uses chemicals and paper to contain and refract light.

Susan Chafe, How the Iron Age Began, 1987.

Also fascinating is the correspondence between the shadowy, ethereal images of video in the back room, and the sub-text of the play between dark and light that we find in many of the pieces exposed to the narrative sound coming from that box of batched electronic impulses. The literally tarred and feathered Dear Winnipeg, by Sharon Alward, with its humour and shadow of racist repression, and the almost stark white ethereality of Kim Ouellette’s painted sculptural installation, Untitled, are only two examples of the other-worldly immediacy that is ‘mirrored’ in the back half of the gallery. And in that video-added context, Marcel Gosslin’s L’Arbre becomes a kind of emblem, a reminder to look more closely for the shadow behind playful ironies. L’Arbre is art incorporating nature—but nature is a hibernating tree (if not a dead one) and its light and barely visible shadow is literally a blood red maple leaf, bleeding.

Which brings us to the other side of 1987. By definition, 1987 is a Big Deal Show, with lots and lots of work to do. Not only is it a NOW show to 1912’s international THEN, but it is travelling around to some small but significant galleries to represent both the sophistication and the regional spark of Manitoba’s contemporary art. And, regardless of intention, it will be seen to represent the curators’ vision of how best to select and exhibit the work of Manitoba artists—artists who must work like Clydesdales to communicate with mass audiences and compete like Arabian thoroughbreds in the international races to accomplish this. 1987: The Catalogue is, therefore, all the more a critical tool.

Don Proch, Ancestral Mask, 1987.

The WAG should be commended for the complete listing of the selected artists’ biographies and works, and for the extensive photographic documentation. Madill’s strategy of including short introductions and leaving space to speak about each artist in the Painting, Sculpture and Performance Sections is not only consistent with her goal of avoiding the imposition of themes that might interfere with the integrity of the works themselves, but is also a gesture of recognition of the artists’ individuality. Similarly, her style of collaboration gracefully allowed the other curators (Michael Cox, Carl Nelson and Charles Scott), to operate autonomously in their own areas of responsibility. Furthermore, the documentary style of the catalogue is consistent with the argument that, despite the recognized peculiarities associated with working in the geographically isolated ‘region’ of Manitoba, no obvious themes or ‘unifying styles’ emerged in her examination of the work being done. To have chosen, then, to include more analytical and/or “theme” essays by curators and/or outside observers, would, according to this argument, have endangered the goal of having the work speak for itself.

This is where the shadows come into play, some of them, of course, as left-hand compliments. The first of these is that 1987: The Exhibition is more successful than 1987: The Catalogue. The exhibition achieves a vitality and excitement in part because it does invite and inspire an active response to the mountain of work in unorthodox and sometimes bizarre juxtaposition. It is also more consistent with the stated goals of the show (one of which is to reveal the “pattern of production”) and with the character of the works themselves—most of which involve multiple and layered interpretations. The catalogue argues that “there appear to be some mutually shared concerns, commonality in themes and recognizable stylistic influences,” and many of these concerns do emerge more clearly as the sought-after “patterns of production” in the exhibition itself. They are much more conspicuously absent in the catalogue. One important reason is that while the installation of the exhibition does celebrate the crossing of borders, the catalogue actually blurs those crossings. To organize an exhibition which not only celebrates the liberation of the spirit of art from categorically conventional habits of thought and perception, but also exposes the patterns of production facilitating that liberation, is a major breakthrough. To then produce a catalogue that seems to deny the breakthrough is a cause of confusion, if not a simple disappointment. ♦

Janis Runge is a Winnipeg freelance writer. This is her first contribution to Border Crossings