1973: Sorry, Out of Gas

The Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) has mounted a prismatic retrospective study of energy shortfall and proposed architectural solution in “1973: Sorry, Out of Gas.” At once powerfully engrossing and overwhelmingly topical, the exhibition is the first to focus on the 1973 oil crisis, when the value of oil leapt to staggering heights, sparked a global crisis and brought forth a wealth of architectural innovations in its wake. Replete with photographs, TV footage, architectural drawings, books, pamphlets and other artefacts, even board games, the exhibition investigated all manner of arresting and inventive architectural responses to the crisis.

Steve Baer, designer. House of Steve Baer, Corrales, New Mexico, 1971. Photography © Jon Naar, 1975/2007. All photographs courtesy Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal.

The wholesale chaos that broke out worldwide in 1973 (one among many memorable instances throughout North America were interminable waits and astronomical costs at gas stations that frayed nerves and resulted in innumerable melees) could very well happen again. Politicians tried to calm the restless masses at that time with, at best, mixed results. The silver lining was and remains, of course, research and innovation, social experimentation and the swiftly accelerating development of renewable energy sources that were all to have a seismic impact on the field of architectural practice.

The oil crisis sent the global economy into a tailspin and generated a palpable sense of global anxiety. On October 17, 1973, OPEC announced a 5% drop in oil production and a significant increase in the price of crude. The cost of a barrel of oil escalated from $2.59 (USD) at the outset to $11.65 at the beginning of 1974. This escalation is perfectly mirrored in recent events as reported on CNN—not incidentally, I think, a few bare months after the CCA exhibition had opened. The show itself borrows its title from the ubiquitous signage so often seen at gas stations across North America in 1973 and teaches that we are perhaps destined to see those signs again.

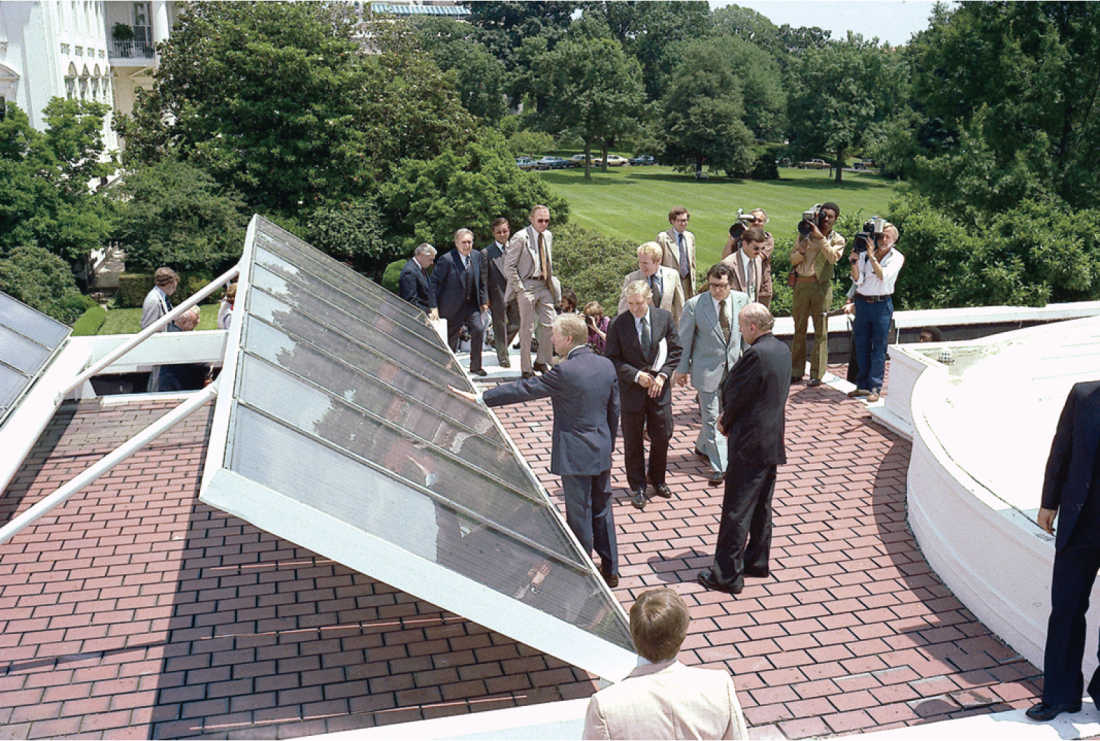

American President Jimmy Carter dedicates the White House solar panels, 20 June 1979. Photograph © Jimmy Carter Library.

For those of us who lived through the oil crisis, and experienced it vicariously once again in this exhibition, and with our children’s futures foremost in mind, it was difficult to remain indifferent or unmoved. Difficult, too, not to feel a binary sense of déjà vu and clairvoyance when confronted with today’s newspaper headlines and television news coverage of a souring US economy and unheard-of prices for a barrel of oil. The exhibition brings new pungency to the phrase “been there done that,” only now, from where we are situated in the present, we are in no way done with that: oil is a rapidly diminishing resource and our continuing dependence on it means that another, more serious oil crisis is perhaps just hours, days or weeks away. So, if the CCA is looking backwards in this show, it is also, I think, looking ahead. It is eerily prescient and does an exemplary service in tweaking our still-slumbering, collective social conscience.

The exhibition presented viewers with a cornucopia of innovative thinking and a high level of formal invention in the face of the past crisis. Archival TV footage of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau addressing the country was especially interesting, if viscerally disappointing, reminding us that our otherwise visionary PM once assured us that a voluntary program would suffice: “Our current assessment is that all rationing at the retail level will not be necessary.” Here was at least one glaring political example of the larger myopia.

Line-up at a Los Angeles gas station in anticipation of rationing, 11 May 1979. Photograph © KPA/dpa.

The exhibition was organized thematically and to brilliant effect in the following categories: (1) Austerity, revealing, without cosmetic gloss, the true impact of the oil crisis on citizens’ habits and lifestyle; (2) Passive Solar, which looked at efforts to convert contemporary building design to take advantage of solar heat; (3) Active Solar, which investigated the evolution and application of technologies to store and convert the sun’s energy; (4) Geopolitical Consequences, an assessment of the fallout and response in the cultural and political domains; (5) Insulation and Underground Buildings, which featured efforts to conserve energy and integrate buildings within their natural circumstances and surrounds; and (6) Wind, which tracked the development of earlier wind turbine designs for rural areas towards finding new applications. Finally, (7) Integrated Systems outlined projects involving food production and the larger social context.

While it is impracticable to cover all these thematic groupings, I should point out that one of the most arresting responses to the energy crisis was surely the development of active and passive solar technologies, with actual samples of the solar panels in question. We were reminded that, in 1979, then US president Jimmy Carter had the smarts to oversee the installation of a row of solar panels on the roof of the White House, designed to heat the presidential water supply. (Revealingly, Carter’s successor, Ronald Reagan, the sycophant of imaginary super-abundance, had them removed seven years later, sending up a high-five that the crisis was over and that everyone could and should return to their normal lives of wanton, ever-greater consumption.) Both the Passive and Active Solar categories showcased singular projects, such as an independent urban effort in downtown New York City—the 519 East 11th Street cooperative— which installed solar panels and a wind turbine on its roof, towards achieving a measure of energy self-sufficiency.

Solar collectors installed on roof top at 519 East 11th Street, NYC, ca. 1976. Photograph © Jon Naar, 1976/2007.

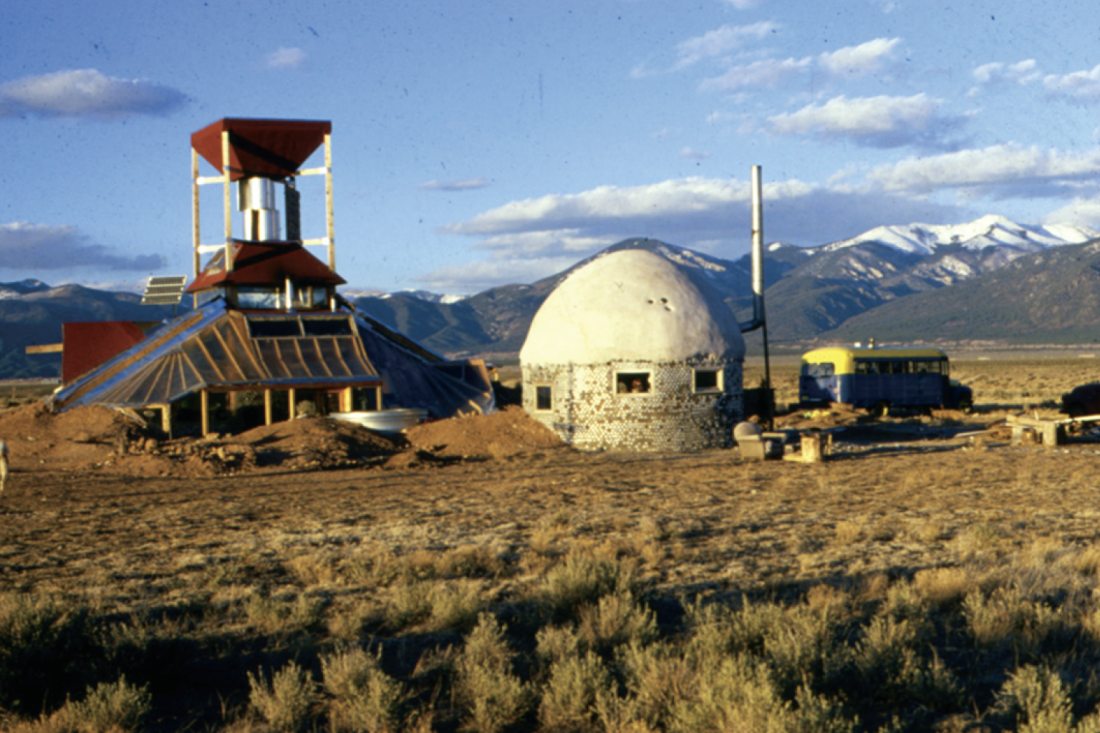

The work of architects who integrated alternative concepts of energy use in the functional design of their building projects was also emphasized, most notably in the work of Steve Baer, Michael Jantzen, Douglas Kelbaugh, Michael Reynolds and Malcolm Wells. Visionary engineers like George Löf and Maria Telkes were also featured for their remarkable development of the active solar power technologies. Beyond the initiatives of individual architects and engineers, both in remote locales and in the urban inner city, the curators reminded us that academic institutions were not remote ivory towers but were also occupying the foreground of the response, perhaps the most notable being an ongoing research program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which has been studying the applications and benefits of solar energy for the last 70 years.

The exhibition also looked closely at the architectural innovators like Montreal-based Ecol Operation, Farallones Institute and Integrated Life Support Systems Laboratories. Their efforts count among the most thoughtful architectural responses to the 1973 oil crisis. On the lighter side of the whole equation was a display case full of vintage board games, like Oil Power, from companies banking on the crisis as a means of enlivening the nation’s living rooms, even as those playing the games were emptying their wallets at the gas pump.

Michael Reynolds, architect. Turbine House, Taos, New Mexico. Photograph © Michael Reynolds, 2007.

If the exhibition meant reappraising where we have been and what was learned, it also showed us with rare perspicacity just how much was lost and forgotten as we all collectively put the blinkers back on and resumed business as usual later in the 1970s. It was precisely what was not enacted in terms of solution and resolve, at least on this continent, that makes our present predicament so acute and, frankly, so poignant. Perhaps the most pressing and awkward question we asked ourselves amidst the vast acreage of documents, photographs, TV footage and other materials in the exhibition (that so meticulously tracked the oil crisis, resultant fallout and architectural responses in their multiplicity) was: how could we have forgotten so much so quickly and, in the face of this blind spot, what will we have to remember now and in future in order to change? Or are we destined to repeat history, and fall by its wayside? Perhaps because the answer is cultural, not technological, as the exhibition demonstrates, the answer to the question must remain speculative. Nothing less than a paradigm shift in thinking is needed. The exhibition is hence both a timely meditation on energy waste and husbandry and, it is hoped, will be a potent catalyst for, and perhaps harbinger of, quantum change in the condition of being here, in an increasingly energy-strapped world.

CCA Director and Curator Mirko Zardini certainly sounded the right note in his insistence that contemporary architects look closely and then more closely still at the innovative work of their confreres from the 1970s in order to tackle similar issues today and to engage in continuing research.

Installation view of “1973: Sorry, Out of Gas.” Exhibition design by Gilles Saucier, Saucier + Perrotte Architectes. Photograph Michel Legendre © Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal.

Co-curators Zardini and Giovanna Borasi are to be commended for their exhaustive and telling efforts to increase public awareness in documenting the crisis and response through a vast array of hundreds of vintage objects, including photographs, books, archival television footage and architectural drawings. More importantly, perhaps, they have effectively tweaked our collective social conscience and awakened it from its long hibernation, alerting us to the old truism that says that humankind is enmeshed in a web of sleep and dreams— woven mostly by ourselves. Their “wake-up call” is clarion, unmistakable and true.

This is the first exhibition curated by Zardini in his position as CCA Director and Chief Curator. (As Visiting Curator he had curated the CCA exhibitions “Sense of the City” in 2005 and “Out of the Box: Price, Rossi, Stirling + Matta-Clark” in 2004.) CCA Curator of Contemporary Architecture since 2005, Borasi curated the groundbreaking and related exhibition “Environment: Approaches for Tomorrow” (2006) on the work of Gilles Clément and Philippe Rahm, recently reviewed in these pages.

In its recent exhibitions, and once again in “1973: Sorry, Out of Gas,” the CCA has set a high benchmark for state-of-the-art and user-friendly production and presentation values based on sound scholarship and through elegant and deft installations. Further praise to Montreal-based architect Gilles Saucier of Saucier + Perrotte Architectes for an exhibition design that hooked viewers from the get-go, and propelled them through the exhibition’s halls with unusual fluency to myriad oases of interest, and with multiple entry and exit points. ■

“1973: Sorry, Out of Gas,” curated by Mirko Zardini and Giovanna Borasi, was exhibited at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal from November 7, 2007, to April 20, 2008.

James D. Campbell is a writer and curator in Montreal. His recent publications include Cheese, Worms and the Holes in Everything: David Blathwerick (Art Gallery of Windsor, 2008), A Mind of Winter: The Art and Thought of John Heward (Musée du Quebec, Quebec City, 2008) and On the Inside: Janet Werner (Parisian Laundry, Montreal, 2008).