1912: Traditional Avant-Garde

1912: Break Up of Tradition is the boldest step the Winnipeg Art Gallery has taken since Carol A. Phillips became Director in 1985. It marks the 75th anniversary of the gallery with a new scale of ambition. Substantial catalogues and a series of distinguished public lectures support it and its energetic companion exhibition: 1987: Contemporary Art in Manitoba.

When Phillips was appointed no plans were in hand to mark the anniversary. Then, 18 months of frantic work went into preparing the 1912 show. The results on the walls and in print are mixed but the direction of the effort is obviously correct. Clearly, a more vital and interesting program is emerging under Phillips’ ambitious leadership.

The 1912 exhibition attempts to be a small-scale block-buster of advanced art from, essentially, the year the Winnipeg Art Gallery opened. Unlike the 1914 exhibition with which the Baltimore Museum of Art celebrated its 50th anniversary in 1964, the 1912 show elects not to survey a variety of styles but to concentrate on the art which now rejoices in the rather liberally applied epithet, ‘the modernist avant-garde.’

This creates a curious situation. Why this show in Winnipeg now? Do Cubist and Expressionist European art of 1912 offer any parallel to the Canadian landscapes, lent by the Royal Canadian Academy, which officially opened the WAG’s first quarters in the Winnipeg Industrial Bureau in December, 1912? While the gallery spoke of Winnipeg as “the financial capital of western Canada, striving for new culrural sophistication amid a climate of civic confidence and rapid growth,” there was only the most tenuous link with the new European art of that date.

In one sense Cubism and Futurism are appropriate to evoke Edwardian Winnipeg. These schools comprise the bottled history of classical modernism that has become a commonplace of our textbook view of art before World War One. In 1912, the pluralism that has integrated recent scholarship on the 19th century had only just begun to make inroads. Stephanie Barron’s mistitled but electrifying German Expressionist Sculpture for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1983, in which many styles were mingled, showed the way. There, she allowed that every work of art is unique and at the same time universal. As curator, Barron recognized that the museum in its role of educator needs to find a way to make each piece speak for itself, not just reinforce a simplistic label.

Louise D’Argencourt, guest curator of 1912: Break Up of Tradition, subscribes to the heroic view of modernism. This is Louise D’Argencourt’s 1912: the spiritual values which “comprised the keystone of the vault of metaphysics and mysticism that dominated … the avant-garde from its beginnings in the nineteenth century until its glorious apogee in the twentieth.”

A curator with four big exhibitions behind her (Puvis de Chavannes and the Tannenbaum Collection for the National Gallery in Ottawa, Bouguereau and Jacqueline Picasso’s Picassos for the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts), D’Argencourt certainly has the international contacts to make the project fly. The failure to get various pieces stems from a late start, bad luck, and of course, in this league, a certain lack of institutional whack. Added to this is the growing reluctance to lend to thematic rather than monographic, single-artist shows or to lend works of the first rank at all. It is a strong collection that receives Matisse’s Red Studio, a 1912 painting on loan from the MOMA in New York.

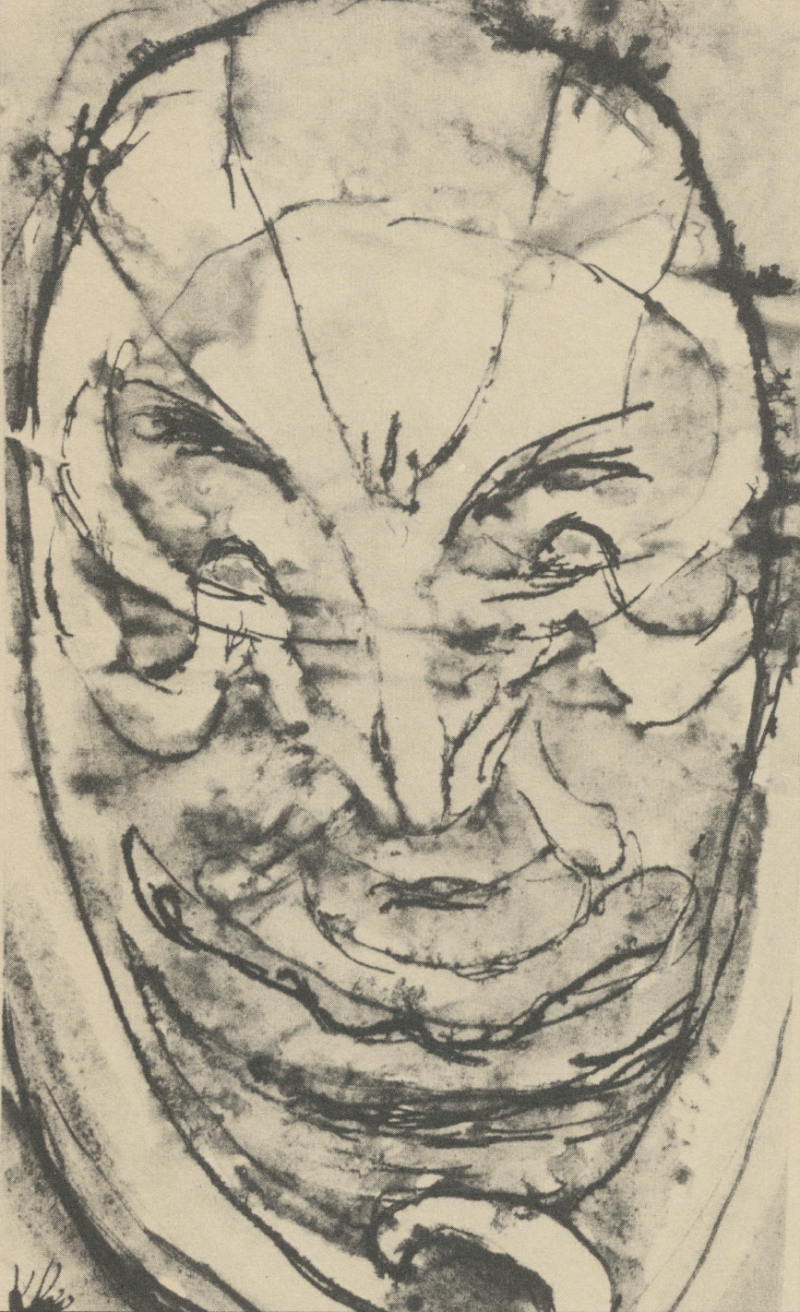

In the Winnipeg show, in terms of sheer quality, there are several high points: Kandinsky’s big Improvisation, Sketch 160a from Houston, Picasso’s J’aime Eva from Columbus, Ohio, and a small ink and watercolour face by Paul Klee (Man with Blue Eyes) that is startling in its concentrated emotional power.

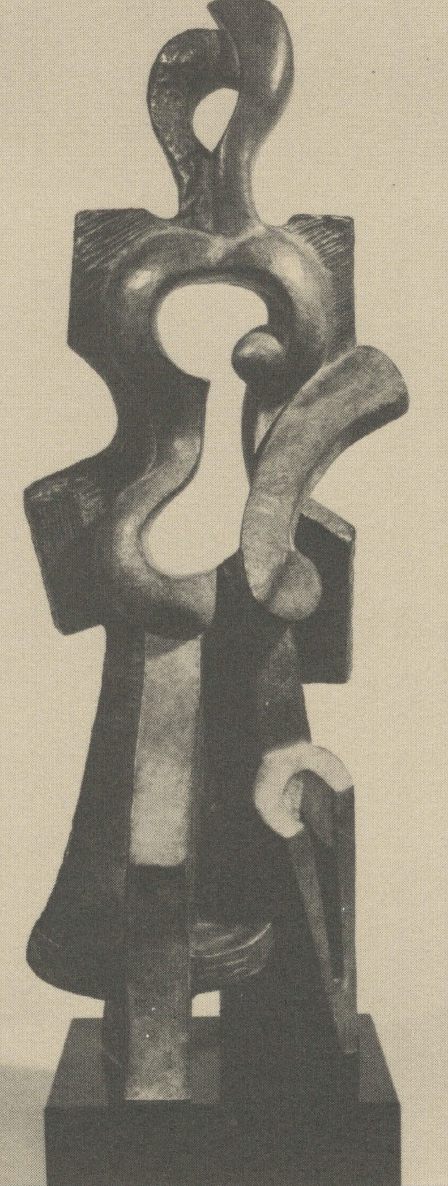

All the sculpture is good—a redeeming quality in an ambitious but disappointing show. There is a fine, little, see-through, standing figure by Alexander Archipenko, an unfamiliar, top-heavy, staggering muscleman by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, one of the arresting and troubling “Jeannette” heads (versionV) by Matisse. Three bronzes by the unjustly neglected Otto Gutfreund are a coup. This momentary leader of cubist sculpture, a Czech then working in Paris, was an artist whose recognition was late in coming.

The catalogue photography is magnificent, particularly of the sculpture. Raymond Duchamp-Villon’s Head of Maggy is stark and depersonalized, like the piece. The Lipchitz is better than the original! With significant pieces by Maillol and Bourdelle to preface the cubist work and a towering Brancusi to append it, the sculpture ensemble stood up well enough to be worth the price of admission alone. That exhibition patrons were happy to pay $4 to see the show was, in itself, a healthy sign for the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

Paul Klee, Blauäugiger/Homme aux yeux bleus, 1912.

Proud as the organizers were to have secured Juan Gris’ famous Man in Café, 1912, from the Arensberg Collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, this overrated artist’s stock has been crashing. Critic Adam Gopnik, in the summer 1984 Art Journal, and historian Malcolm Gee, in a 1979 issue of Art History, share the view that Gris’ fame rests more on his dealer’s successful posthumous manipulation of the market than on intrinsic merit. Still, the number of works loaned by major collections, such as Philadelphia, evokes admiration.

Ones that got away: a major German-owned Kandinsky that became a centre-piece of the L.A. County Museum’s The Spiritual in Art; Abstract Painting 1890-1985 exhibition last fall; a promised Brancusi Bird in Space which was only partially made up for by the substitution of a Maiastra piece on a limestone and wood base which makes it the largest sculpture piece in the show; even the renowned Nude Descending a Staircase, Number Two which was verbally promised until Philadelphia realized that 1987 would be Duchamp’s 100th anniversary. There was no major (or minor, for that matter) Matisse oil—a very serious omission to which Phillips is the first to admit. The Futurism & Futurismi exhibition last year at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice precluded other loans. Alas, by the luck of the draw, in choosing this show the organizers hit several major artists when their work was in rapid decline. By 1912, Derain and Vlaminck had passed their momentary Fauvist glory and Munch had suffered the electric shock treatment that ‘cured’ him of alcohol, tobacco, sex and talent.

It was interesting to note that one of D’Argencourt’s best ideas failed to work in several cases. This was to mount contrasting examples of works by the same artist which might illustrate how his style was toughening up in the period 1911-1914. The goal was achieved successfully by the pair of Bonnards, but rather the opposite effect was produced by the pair of Kandinskys. There, the later one, which is supposed to be “better” by the heroic and progressive model of more-abstract-is-better, is simply not.

The layout of the exhibition was not what viewers in the 1980s have come to expect. Intentionally so. It sought to evoke the first consciously modernist exhibition, that of the Cologne Sonderbund in 1912, where, for the first time, the walls were painted white and works spaced out in single file along them. Unfortunately this subtlety was overlooked by most viewers, even expert ones, since this format has since become universal. More could have been made of this in the catalogue, although the exhibition was half over before the lavish book appeared.

D’Argencourt’s strongest contribution is the focus on new Soviet art. A dozen Soviet or proto-Soviet artists were presented, unfortunately all by minor work, yet this is where the catalogue earns its value as a scholarly tool and lasting contribution.

D’Argencourt’s next major exhibition, for which she presently is spending six months in the Soviet Union, will be on these artists. References to Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova permeate the book. D’Argencourt added her own short texts on the seminal Russian exhibiting groups such as The Donkey’s Tail, The Golden Fleece, The Jack of Diamonds, and The Target. It remains for intrepid western curators like D’Argencourt to write the history of early modernism in Russia. Now western professionals are welcome to study archives and collections which are not accessible to ordinary citizens in the Soviet Union.

As well as familiar artists, such as Malevich, Liubov Popova, and Alexandra Exter, there is a flying wedge of new names. Some of the biographical entries on these artists are more interesting than the minor work which is shown: Vladimir Burljuk, who died young in the First World War; Leopold Survage, who moved to Paris and stayed there: Nadezhda Andreevna Udaltsova, whose pedestrian cubist still-life graces the cover. In these biographical sketches, major questions remain, but the uniform attacks on tradition voiced by the artists, which are reproduced in a special section of the catalogue, add to the monolithic flavour of this book.

Some confusion exists about whom the catalogue is written for. While the biographies are descriptive and presumably for a general audience, the bibliographies do not always list major titles available in English and we are left with the specialist material in French on which the author has relied. What might have been helpful was reference to the work of Sharon Hirsh on Hodler (1982), Carol Mann on Modigliani (1980), Bryan Robertson on Dufy (1983), John Elderfeld on Derain/Vlaminck (1976), or Sasha Newman on Bonnard (1984).

Writers such as Robertson, Newman, Mann and Barron are challenging the view that there is a simple scale of virtue in direct proportion to the degree of abstraction or to the complexity of the work of a given artist. Elsewhere, there is a new interest in hitherto neglected artists of this period, Gwen John for instance, or Suzanne Valadon. There is no hint here of the massive Edwardian revival that is on right now: Orpen, Sargent, Boldini, or sculptors Alfred Gilbert or George Frampton (whose Queen Victoria sits facing the WAG from her throne in front of the Legislative Building). So D’Argencourt’s Parisian bias, even acknowledging the Russians, many of whom touched base in Paris, permeates the show. Even the dreadful Prix de Rome winner of 1912, Oedipus Crying over the Bodies of His Sons by Gabriel-Charles Girodon, is included. But interestingly, there is no Klimt, no Klinger, no Minne, no Meunier, no Sickert, no Steer.

This is textbook Modernism with a capital M. It is the kind of eminently teachable A-leads-to-B art history which results in handouts like the one-dollar flyer, “Interpreting the ‘Isms,” which John Bentley Mays cruelly but accurately called “a sort of birdwatchers’ guide, complete with pictures and descriptions of the plummages associated with each style.”

Alexander Archipenko, Walking Woman, 1912.

Without actually discussing the works presented, we are left to guess what D’Argencourt makes of individual works. With such blanket endorsements as there are, the implication is that if an artist is here, beyond the tame offerings of room one in the gallery, then she or he is ‘good.’ If they were stuck in room one, the implication is that they were mired in reaction. Included in this category are: Maillol, Bourdelle, Corinth, Hodler, Denis, Vallotton, Bonnard, Marquet, Renoir and the truly stilted Girodon. Yet we should not have to guess what a curator is trying to tell us.

The message of the 1912 show is formalist. The largest room brims with Cubism. Off in the back is Expressionism. The final room holds Abstraction with heroes Larinov, Sonia Delaunay, Kandinsky, Picabia, Kupka and the towering Brancusi. To penetrate to these mysteries we must endure Representational art, a lower state of being, in room one.

No room has a monopoly on weak works. There are frighteningly bad pieces throughout the show: Villon’s Man, Herbin’s Still-Life which misunderstands every tenet of Picasso/Braque’s Cubism, Freundlich’s Composition, Souza Cardoso’s ink nude, Munch’s miserable landscape, or Anisfeld’s jungle Eden, to name a few.

1912 was not a radical year in Winnipeg. In fact, with the opening that year of the Panama Canal, there were grand expectations for this ‘Chicago of the North’ as a continental transportation hub which peaked and just as quickly faded. Avant-garde European art of 1912 did not destroy tradition, either. It grew out of the various post-Impressionisms and established its own new traditions which have become our orthodox view of that era.

Manitoba art of the same era will be offered in a subsequent exhibition. Currently, the Winnipeg Art Gallery is mounting Vistas of Promise, Dr. Virginia Berry’s follow-up exhibition to A Boundless Horizon of 1983. This gathers Manitoba art of the period from 1874 to 1919. The gallery hopes to be able to mount a third show in the future that would carry the theme up to 1950.

When, as in the 1912 show, everything is avant-garde, nothing is avant-garde. The real test is not whether these works wear better than the frightful Girodon (sure evidence of a fatigued academic tradition past the point of exhaustion), but whether the groupings here would have meant more to the gallery just starting out than a selection of the best semi-modern art of 1912. For instance, would more interest have adhered to works by Klimt or Sloan or Sargent?

What we are given here is meant to be ‘good’ for us, following the now-shopworn doctrine of the spiritual aspirations of heroic Modernism. All this as if the last 10 years of post-modern debate challenging this view had not taken place. This is the art we are supposed to admire. In fact, it is the art we used to be required to admire. There is no denying the wizardry and beauty of a Red Studio or the cutting edge of a Demoiselles d’Avignon but there is nothing edifying about the debased exercises of their commonplace clones, so much of which constitute this exhibition.

Just as this curator was parachuted in from Paris and Montreal, so too, the spear-carriers of tired old modernism have been marshalled for Winnipeg’s 1912 anniversary. The Gallery’s heart was in the right place but this show displays thinking as tired as the R.C.A. landscapes of the original 1912 show did in their time.

When there is only Good art and Bad art, the curator’s conceptualizing is arrested at a rudimentary level. Why are the works not examined individually and in detail in this catalogue? Would too many wither under the scrutiny? Or was it merely sheer haste and too little idea of what was coming? Either way, the catalogue serves as a thick and glossy legitimization of the exercise, rather than as a critical document of lasting value.

Saskatoon with Eric Fischl, Calgary with The Dinner Party and Edmonton with David Milne: The New York Years have mounted recent exhibitions of more than local interest. When Carol Phillips was director of the Norman MacKenzie, so did Regina. The 1912 show is a misnomer. It is not a Break Up of Tradition, it is tradition. But it is a surge of energy, nonetheless. The new boss who brought that energy has achieved much in her boldest undertaking to date. The curatorial myopia of the 1912 exhibition should not preclude the goal the director so clearly intends to gain: truly national status for the Winnipeg Art Gallery. ♦

Dennis Sexsmith is an Assistant Professor in the School of Art at the University of Manitoba. This is his first contribution to Border Crossings.