Now and Then

If Michael Snow were an animal, he’d be a cat. He has had at least nine lives: filmmaker, sculptor, painter, record producer, faux ethnomusicologist, and two kinds of jazz musician. In his most recent life he has become something he has never been before: an orchestral composer. In January the 2018 Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra’s New Music Festival will premiere Prophecy, a 40-minute-long glissando involving the entire orchestra. “At first it will seem like a drone and then you’ll become aware that it is gradually rising,” Snow says. “It will go from the very lowest base instruments, through the various arrangements of the strings and brasses and woodwinds. There is no harmony, it is just continuously changing colour.”

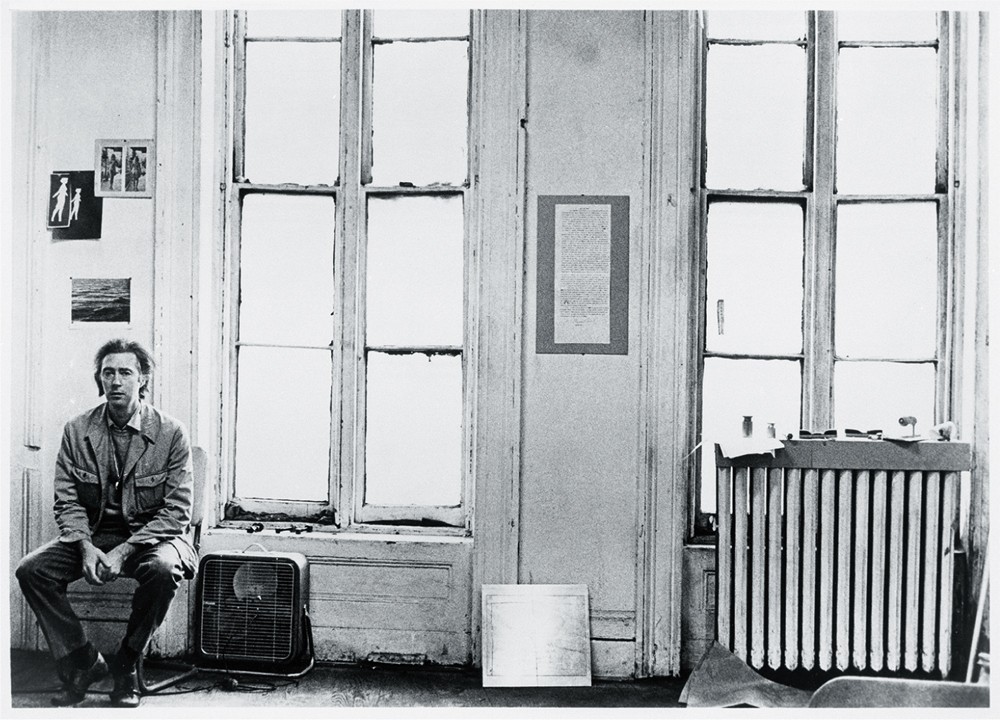

Michael Snow in his “Wavelength” studio, circa 1969.

Snow’s naming plays off the composition’s sense of movement: “At different stages you’ll appreciate that it has come from somewhere, which is the past, and the present because it is moving in time, involves a prophecy as to where it’s going.” The connection between the past and the present is contained in his notes for Wavelength, published in Film Culture in 1968. Snow writes that his film “attempts to utilize the gifts of both memory and prophecy which only music and film can offer.” His composition is the receiver of the gift his film has made available. As an artist, Snow has always been a genre-crosser. With Prophecy, he has made music by a filmmaker: “When I received the commission I thought about the different things I could do and the different directions I could take. What interested me was the idea of somehow making a version of the glissando.” Prophecy became a meeting of then and now.

In Toronto and New York in the ’50s and ’60s, Michael Snow was a different kind of cat, playing in jazz clubs and attending performances by the Coltrane Quartet, La Monte Young and Charlemagne Palestine. “There was a bunch of things happening in music that were just extraordinary,” he remembers. He also met Philip Glass and Steve Reich: Reich because he admired Wavelength and had written to Snow that he wanted to meet him; and Glass because he was a part-time plumber. “Living in lofts was illegal at the time, so a lot of work with wiring and plumbing was done by underground tradesmen,” Snow says. Two men did some plumbing work and then left their box of tools in the loft. “I called them and said, ‘Your tools are here,’ and they said, ‘We’ll come tomorrow,’ but they never did.” Snow found out later that his forgetful plumbers were the composer Philip Glass and the sculptor Richard Serra.

Serra’s studio was close to Snow’s and the two became friends. “Richard was voluble and interesting and genuinely wanted feedback. I thought he was doing wonderful work, including his films, which were obviously tied to his sculpture,” Snow says. Serra returned the compliment. When he was included in two exhibitions in Europe in 1969, he took Wavelength with him and screened it in cinemas and film archives. “I liked the zooming in and monotony and strangeness, the play on suspension and even a little Hitchcock,” Serra says. “And the humour and sarcasm and thumbing its nose at Warhol. I thought it was a great film.”

There was a sense of reciprocal appreciation for what everyone was doing. When Steve Reich was asked to perform his Pendulum Music, a composition scored for four microphones, at the Whitney Museum in 1969, he selected artists whose work he admired to be the mic-releasers. He chose Richard Serra, Bruce Nauman, James Tenney and Michael Snow. Almost 50 years later, Snow remembers the performance: “I was very honoured to be part of it.” ❚