“About Face: Photography by Cindy Sherman, Laurie Simmons and Rachel Harrison”

This welcome and timely gathering of the works of three important American feminist artists who have all engaged in a deep and sustained dialogue with the history of female representation—Cindy Sherman, Laurie Simmons and Rachel Harrison—constitutes a united front against imagistic orthodoxies and stereotypes. The show is replete with some of their finest images. Notably, the works in the exhibition all come from the collection of Carol and David Appel, astute collectors of international contemporary art.

Sherman, the most august and subversive of creative chameleons, nimbly pirouettes here between Self and Other. She does so with phantasmal ease, cunning dissemblance— and cathartic grace. She hosts her own several identities in body doubles that inhabit the horizon of similitude with all the genius and savvy of Jonna Mendez, the illustrious former chief of disguise at the Central Intelligence Agency in Langley.

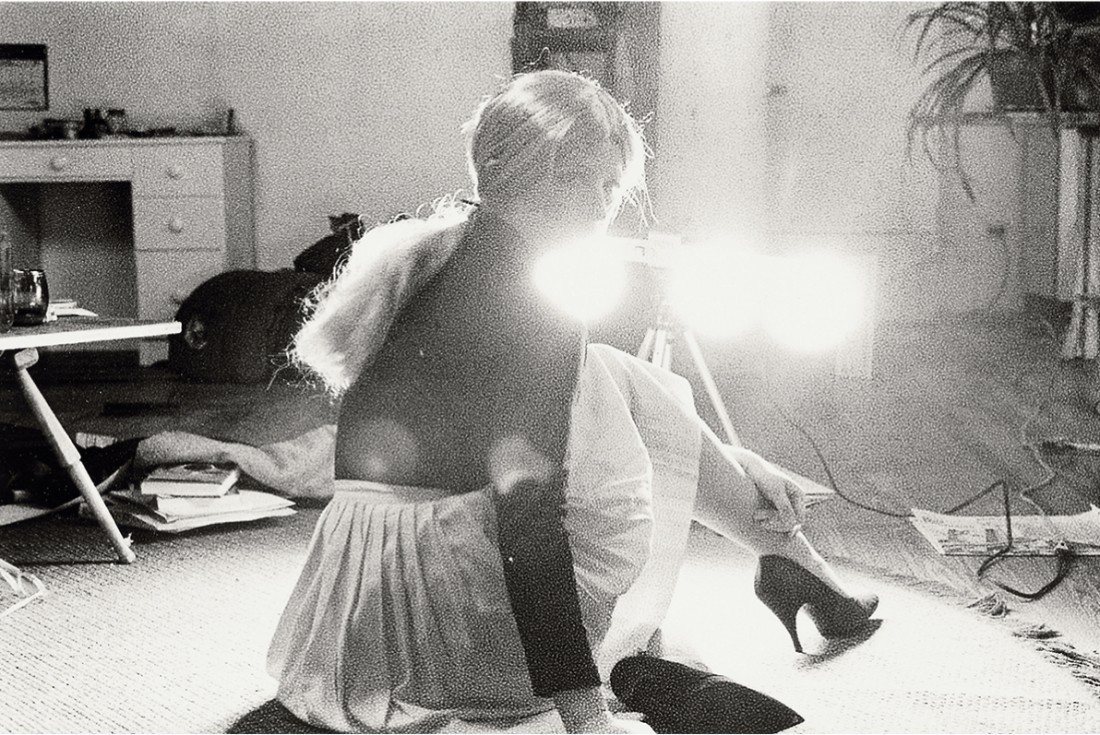

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still no. 62, 1977–2003, gelatin silver print 2/10, 20.3 x 25.4 centimetres. Loan, collection of Carol and David Appel. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Sherman has assumed sundry personae and photographed herself with dexterity as a shape-shifter. With a daunting inventory of apparel, hairstyles, costumes, makeup, props and even prosthetics, she has pushed her chameleon practice through several hoops that deny, defy and deify an otherworldly order of narcissism. Her images have aged well. “Murder Mystery” works, 1976–2000; “Untitled Film Stills,” 1977–1980; “History Portraits,” 1988–1990; and “Surreal ist Pictures,” 1995–1996, all argue the case that her work still rules after all these years, and her remarkable panoply of images pivots between dissemblance and resemblance, high and low fiction, performativity and something like rapture.

The show features an exceptionally rare complete set of Sherman’s “Murder Mystery” series that was a delight to experience once again after all these years. This assembly of 17 small black and white full-length self-portraits is arguably one of the artist’s strongest. Each portrait captures a different persona derived from characters found in fiction and constitutes one step needed to unlock meaning, like a Japanese puzzle box. Untitled Film Still No. 22, 1978, will be instantly recognized by many viewers, although the works in that series of the artist depicted in the guise of various generic female film characters are not considered self-portraits per se. Sherman is also her own heterodoxical subject in the “History Portraits” series. She radically inverts the conventions of historical portraiture and raises a changeling in its place.

Another fellow traveller and leading representative of the Pictures Generation, Laurie Simmons, is represented by a single major work, Walking Camera II (Jimmy the Camera), 1987, which comments ironically and playfully on the relationship between the photograph and the representation of the female body. Walking Camera I and II (Jimmy the Camera), 1987, are a tribute to Jimmy de Sana, who died of AIDS in 1990. The shapely legs in ballet leotards emerge like a tripod beneath a humongous antique bellows camera. (Its companion is in the collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art.) But this single work more than makes up for the paucity in its scale and gravitas.

Rachel Harrison, Voyage of the Beagle, 2007, (detail). Carol and David Appel Collection. Courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali, New York.

Simmons’s fictions scintillate as they explore the dark side of the American dream in images that question the idylls of prosperity and feminine domesticity while upending all the conventional wisdom about photography as a medium.

Sherman’s and Simmons’s work is placed in chiasmic dialogue with the equally feisty and uncompromising work of Rachel Harrison, a maverick and polymath whose Voyage of the Beagle, 2007, sets out an ironic and instructive itinerary— and is an intoxicatingly brazen hodgepodge of images named after Charles Darwin’s 19th-century field journals. Here, she explores a compelling medley of figural and sculptural representations of the body drawn from the most disparate and often unorthodox of sources.

The reference to Darwin’s journals is both ironic and just but never glib. Comprising 32 of 57 pigmented inkjet prints, Voyage of the Beagle is a compelling testament to the breadth and ambition of Harrison’s voyage in search of the origins of sculpture. First published in 1839, the journals document Darwin’s second expedition on the HMS Beagle, a journey that would later inspire and inform his seminal 1859 monograph, On the Origin of Species. Harrison assumes the role of art’s iconographic naturalist just as Darwin did on the surveying voyages by HMS Beagle. The Journal of Researches lays the groundwork for his theory of evolution by natural selection. Yet, Harrison, for her part, is not an artist in pursuit of utopian signifiers. Quite the contrary: she will seize on the louche, marginal and unlikely in order to leaven her taxonomy with real-life resonance. Her mix-and-match sensibility is solidly anchored in the present moment.

Beginning with a trip to Corsica, where she saw prehistoric stone sculptures that were perfect fodder for her project, and continuing across Europe and the United States, she photographed the good, the bad and the ugly and everything in-between in order to ground her itinerary in the truth of things seen. Tribal masks, cigar store Indians, taxidermy specimens, Gandharan stone busts, store display mannequins—all these and more come under her purview. The resulting miscellany—taxing, exasperating but, above all, riveting— is subject to a visual levelling-off routine that forces us to search out more fugitive linkages from one image to the next, and to assess the strength and tenor of the spectral gravity between them.

Sherman, born in 1954, and Simmons, born in 1949, are recognized as leading figures of the aforementioned Pictures Generation, which emerged in New York roughly between 1974 and 1984 and took photography beyond the document into another dimension of social critique: the surreal and the politics of representation. The youngest artist here is Harrison, born in 1966, and she acknowledges that while influenced by Sherman and Simmons, she values her autonomy, and her work betrays little visible evidence of their influence.

Harrison’s work has deservedly garnered a great deal of attention recently, and none other than the estimable art critic and poet Peter Schjeldahl deemed it “the zestiest” and “least digestible” in the whole pantheon of contemporary art. One small point: if works by Vikky Alexander, also an alumnus of the Pictures Generation now based in Montreal, had been included, those works would have constituted a fourth leg of the exhibition, and would have mensurably added to the lively conversation that unfolded on the walls here.

Curator of “About Face” Mary- Dailey Desmarais has made a most convincing case that the exhibiting artists all perform a necessary about-face on the medium itself, with hugely edifying results. ❚

“About Face: Photographs by Cindy Sherman, Laurie Simmons and Rachel Harrison” was exhibited at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal, from December 11, 2019, to March 29, 2020.

James D Campbell is a writer and curator in Montreal, and is a frequent contributor to Border Crossings.